There’s been another wee outbreak of Scots-isnae-a-language-itis on social media of late. It’s a bit like gonorrhea, you think you’ve got rid of the disease then some wee dick comes along and infects everyone again. There’s a peculiar affectation amongst those who deny the existence of Scots as a language. Because they speak English they think that they’re qualified to make linguistic pronouncements that fly in the face of linguistic orthodoxy. It’s a bit like imagining that just because you’ve just passed your driving test that you’re immediately qualified to design cars for Maserati and you’re a faster driver than Lewis Hamilton.

We ridicule those who want the theory of a flat Earth to be taught in schools, there is rightfully strong and entrenched opposition to calls from religious fundamentalists for their creationist myths to be taught in science classes. The denial of Scots as a language is in the same league. It’s a position held by idiots who don’t have a clue what they are talking about, who substitute opinion for fact and prejudice for learning. Scots-deniers are the linguistic equivalent of people who believe that the world is born on the back of a gigantic elephant. But the only giant elphantine thing that exists in reality is the giant elephant sized turd that these folk drop all over any serious discussion of language in Scotland.

In what is quite certainly a vain attempt to answer these idiots for once and all, what follows in this blog post is not my opinion. It is based on an article by the highly respected Scottish linguist the late Professor AJ Aitken, a man whose contribution to the science of linguistics is so great that he’s actually got a law named after him. Aitken’s Law describes how vowels are realised in Scots and Scottish English (which is English pronounced according to Scots phonology). In 1984 Professor Aitken wrote a paper for a book called Language in the British Isles published by Cambridge University Press. The book was a collection of scholarly articles examining the different languages of these islands, and looking at their sociolinguistic setting. The book is a comprehensive survey of the varieties of speech used in Britain and Ireland, the only one it missed out was the keech spoken by Scottish Unionists.

In his paper, Scots and English in Scotland, Professor Aitken included a chapter called “What is special about Scots?” which directly addresses the issue of the distinctiveness of Scots. Just what is it about Scots that elevates it above the run of English dialect and allows it to claim the title language?

Firstly, Scots is of course not a single dialect, it is a collection of dialects which self-evidently have more in common with one another than they do with anything else that can be called English. While non-standard dialects in England merge imperceptibly into one another, Scots and Northumbrian English are separated by a sharp and deep linguistic frontier which runs, more or less, along the Scottish-English political frontier. Professor Aitken points out that this linguistic frontier is becoming more important with the passage of time, as traditional dialect dies out in England but Scots retains more vigour in Scotland.

Nowhere else in the “English speaking” world is there anything remotely like the sharp and abrupt linguistic frontier between Scots and the English of Northern England. Numerous important linguistic features which are typical of Scots run along this frontier. A border between linguistic features is called an isogloss, the Scots-English frontier is by far and away the most important bundle of isoglosses anywhere within “English”.

Within Scotland, Scots and Scottish English exist in a continuum. Speakers use more Scots or more Scottish English depending on social circumstances and who they are talking to. Scots speakers are more likely to use Scots with family members and close friends than they are in formal social settings like a job interview. Scots isn’t the only language variety to exist in a continuum along with Standard English in this way, the same is also true for English dialects.

However Professor Aitken points out that the end points of the spectrum are far further apart in Scotland than they are anywhere else in the English speaking world. In fact from a structural linguistic point of view, the end points of the Scots-English spectrum are clearly different languages which are not mutually intelligible. Even when Scots words are evidently related to their English equivalents (the technical term is cognate), the phonetic distance between the two is great. The vowel in hame is very different from the vowel in home. As well as cognate vocabulary, Scots also contains a mass of vocabulary which is not cognate with English, words like haiver, stramash, sheuch, speugie, stank.

It’s not just the sheer linguistic distance which makes Scots special. It’s also the quantity of Scots. Professor Aitken was the editor of the Dictionary of the Older Scots Tongue and points out that the Scottish National Dictionary (a dictionary of modern Scots) contains over 30,000 entries few of which are obsolete. No other “dialect” of English has anything approaching this quantity of vocabulary. That’s not surprising when you consider that due to its former use as the national language of the Scottish state, Scots contains literary and formal vocabulary such as legal terms. That means that there is such a thing as formal literary Scots. There is no such thing as formal literary Cockney or Geordie. Scots has registers, English dialects do not.

It’s not just that Scots possesses, in abundance, the sheer linguistic differentiation from English that makes it a language. Scots also possesses a rich and copious literature. According to Professor Aitken:

In quantity, distinction and variety this literature far outshines the ‘dialect literatures’ of any other part of the English speaking world. Scotland is unique amongst English-speaking nations and regions in possessing its own great literature in both ‘standard’ and ‘dialect’ versions of its own language … Furthermore, many Scots, such as Walter Scott and Hugh MacDiarmid, are very conscious that a form of Scots formerly was (in the sixteenth century) the full ‘standard’ or ‘official language’ of the then separate Scottish nation.

It was in its former use as the official language of the Scottish state that Scots began to develop its own orthographic conventions. Most of these spellings quh for wh, or sch for sh, are now obsolete, but some, such as ui for a vowel that is pronounced in different ways in various Scots dialects are still current. It would not be too difficult for a standard spelling for Scots to be developed on the basis of older Scots orthographic conventions, using them in a consistent manner without reference to English.

It’s because Scots is currently written in a spelling system based on English – in effect when writing Scots we write English except when Scots differs from it – that allows Scots deniers to keep claiming that one of Scotland’s national languages is not a language at all. However the weight of linguistic evidence is against them – so gaunie jist shut it, haud yer wheesht ya numpties.

So if you want to decide whether Scots is a language or not, who are you going to listen to? A politically motivated zoomer on social media, or one of the greatest linguists that Scotland has ever produced? Me, I’m going with Professor Aitken.

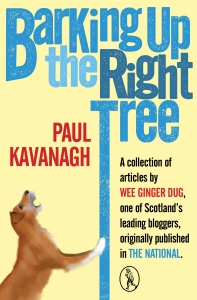

BARKING UP THE RIGHT TREE Barking Up the Right Tree has now been published and is an anthology of my articles for The National newspaper. You can submit an advance order for the book on the Vagabond Voices website at http://vagabondvoices.co.uk/?page_id=1993

BARKING UP THE RIGHT TREE Barking Up the Right Tree has now been published and is an anthology of my articles for The National newspaper. You can submit an advance order for the book on the Vagabond Voices website at http://vagabondvoices.co.uk/?page_id=1993

Price is just £7.95 for 156 pages of doggy goodness. Order today!

A limited number of signed copies of the two volumes of the Collected Yaps is also still available. See below for order details.

Donate to the Dug This blog relies on your support and donations to keep going – I need to make a living, and have bills to pay. Clicking the donate button will allow you to make a payment directly to my Paypal account. You do not need a Paypal account yourself to make a donation. You can donate as little, or as much, as you want. Many thanks.

Order the Collected Yaps of the Wee Ginger Dug Vols 1 & 2 for only £21.90 for both volumes. A limited number of signed copies is still available, so get your order in now! P&P will be extra, approximately £3 per single volume or £4 for both sent together. If you only want to order one volume, please specify which. Single volumes are available for £10.95 per copy.

To order please send an email with WEE GINGER BOOK ORDER in the subject field to weegingerbook@yahoo.com giving your name, postal address, and email address and which volumes (1, 2 or both) you wish to order. I will contact you with details of how to make payment. Payment can be made by Paypal, or by cheque or bank transfer.

The cuddy breezes on the braes

Nane snugger

He pishes on the beachet claes

The bugger

The auld wife runs tae chase

him off

Sae dour,

He turns his arse and lets a fart

The Hooer.

Attr. R. Burns

That yin’s gin in the vault fir future use! 😀

😂😂😂😂 That was just perfect! Aye, we Scots have so much to thank Burns for. Thanks for that.

Reblogged this on pictishbeastie.

I’m with you Boo Boo, Wha’s like us,gie few and there deid

The zoomer yoons are desperate to delegitamize anything that makes Scotland or the Scot unique in the world. Our politics, history, culture, all of it should be made to fade into history and be replaced with/absorbed by their drab grey world. They want conformity and ‘better togetherness’?

Mmmmm… NAW!

Mainly I don’t feel like conforming today and probably not tomorrow either.

I share yir lack i enthusiasm fur conforming tae their grey pishness.

Typical behaviour of the empire builder. But now, as the last remaining colony, we demand our freedom.

They’re going to have to learn fast and muddle along without us.

Thanks for this Paul – it really is about time Scots and Gaelic were put on an equal footing.

[…] What makes Scots special? […]

I’m very keen on languages. Just what floats my boat. I speak Italian, Spanish, Norwegian, a little Swedish, and a few others. I was brought up speaking (Scottish) English, and I’ve studied and picked up Scots along the way.

So –

I’m quite confident when I say that there is more difference between Scots and English than there is between Norwegian and Swedish. There is as least as much difference between Scots and English as between Italian and Spanish.

When I first looked at Norwegian I burst out laughing: “these are all the words we used to get wrapped over the knuckles for using” I thought. The connections are fascinating. And even Norwegian suffers a snobbery between the Danish form and the revived “Nynorsk”

My favourite Norwegian word is ‘Støvsuger’ – which, spoken, sounds awfy like ‘stoorsooker’ – and that’s exactly what it is, a vacuum cleaner 🙂

The German noun for this fabulous device is Staubsauger! 🙂

@ Hugh Kirk

A wee correction for ye Wha’s like us? gie few an thir (they’re) aw died

I just did an on-line course through Glasgow Uni on Burns. It was extremely well subscribed to by people from all over the world. Everyone commented on the richness of the Scots language and how different it was to (English) English. Many commented on how the audience dictated which language was used. The Scottish participants in particular felt multi-lingual as the were able to switch without hesitation from Scots to (Scottish) English and (English) English depending upon the circumstances.

They may have got away with banning the highland dress but they will never take our language.

Weel, aa hae yon buik an a’v taen anither read o’t …

Honestly it does rather reek of special pleading. Scots has held out longer than regional Englishes against assimilation, mainly because it long had its own separate state apparatus, and because the sheer linguistic and geographic distance made it a tougher morsel to digest. And so we have it part-digested, semi-assimilated, with most folk speaking neither one thing nor the other and swithering between the two.

Aitken was writing back in 1984, and seemed to be advocating, pleading in fact, as far as the academic tone of that volume would allow, for Scots to have it’s own place in the sun (or rain or driving snow) as a separate language. OK, but that was over 30 years ago, a whole generation, and nothing appears to have changed.

Scots is still a sort of zombie language, neither altogether dead nor properly having an independent life of its own. Where for example is there a Scots language newspaper? There are several in Faroese, as a quick Google will demonstrate. Faroese then reigns in its tiny homeland, whereas Scots is more like a monarch in exile, maybe one day the king will return, or maybe he’ll just suffer a slow and unpleasant degeneration.

Marconatrix,

my local Asda (Hamilton) has copies of ‘The Gruffalo’s Wean’ and many other children’s books in the Scots language.

A quick search found this book on Amazon, and others, in Scots. There’s obviously a market for it.

Dinnae worry. Schools are responding to the challenge and much Scots is being mainlined again. It’s a guid start!

Aye, aa tae the guid.

But if it’s not done consistently, with some kind of overall scheme, then A pitie the puir bairnies.

A haed the deils ain joab gettin a howd oan Inglish spelling as a kid. I was moderately bright on the whole but since I couldn’t spell I was always being made to look the idiot. But once you accept that English spelling has hardly any more relation to the sounds than Chinese, then at least you can hold on to the fact that each word with a given meaning can only be written one way.

Now there’s little that can be done about English, by now it’s set in stone. But if Scots reading and writing is to be taught, on top of the mess that’s Standard English, then there needs to at least be consistency to the Scots spelling and grammar that’s taught. And it needs to be clearly separated from Standard English, or else both the teachers and the pupils will be all at sea.

@the scottish play

That made me laugh

But What does beachet mean. Ive never heard it and cant find the translation. Is it clean?

sorry my mistake -should have read ‘bleachet’ (white-washed stones/cobbles) = bleached

Ah right. Thank you

Given the dual/opposite meaning throughout (‘he’ turned his arse …versus… f. Hooer) could be claes = ‘clays’ (bleached clays (stones / cobbles as was done at the time) or claes = clothes …though this would be some shot for a male horse onto drying clothes on a washing line… take it up with the Author !.. it wisnae me.

This was verbally recited to me in the presence of alcohol ~1990 and I was told it was attr. to Burns, so you have my spelling/interpretation in what I’ve written.

Should the word perhaps be “bleachet” (bleached) ? That would make sense.

Spot on, Paul!

When I was a boy I used tae laugh at some i the daft words ma Ma used.

I used tae think she made them up (wersh) in her heid.

Noo a realise she wis keepin the auld Leid alive.

Fur me…

Thanks Ma.

O/T Worth a read.

http://ponsonbypost.com/index.php/news/64-gordon-s-vow-the-denial-of-the-saviour

Thanks, Sam. Certainly well worth a read.

That’s one to bookmark for indyref 2 Jan.

Watch some of the excellent subtitled Scandinavian TV shows currently fashionable and you’ll quickly begin to understand where many Scots words came from.

I just don’t understand why anyone would want to argue over what is or isn’t a distinct language.

Its like arguing that a Vespa isn’t a motorcycle.

I also enjoy watching subtitled Scandinavian TV, detective series and suchlike. But a couple of things that made an impression with regard to language were : (1) most people can speak and understand English and instantly turn to English when they need to communicate with a foreigner, whether a Polish lorry driver or a far-eastern business delegation; (2) in stark contrast to that, they do not change to English when speaking to other Scandinavians, but seem to exhibit only the most minor problems of understanding, e.g. the odd joke along the lines of “what a thick accent he’s got” etc.

Now to me this means that on any objective measure of inter-comprehension, all speakers of Norwegian, Swedish and Danish technically speak the same language. Nevertheless they are regarded as separate, e.g. we get three sets of instructions on all those multilingual leaflets you get with gadgets these days.

The reason for this is that there are three separate nations each with its own government and educations system, each of which has sponsored it’s own distinctive written form, with it’s own slightly different orthography, grammar rules and so on. (Or two systems in the case of Norway!) And each of these standards is used throughout most of society, in schools, universities, serious and trivial publications, public signage, pretty much everything in fact.

Each Scandinavian standard overlays a whole bunch of dialects that may well vary as much or more within each country as between. Which dialects look to which written and taught standard is a matter of history and politics, not really of linguistics.

So on this basis there is no Scots language … yet.

Scotland has had a government of its own, in control of education among other areas, for a good few years now. If there was any real demand for a Scots language apart from English, then why hasn’t an appropriate standard been created and universally taught and used? A focus that all the various local dialects can look to?

So at present I’d say there is no Scots ‘language’ in the sense that there are Norwegian, Swedish and Danish ‘languages’, just a bunch of written and spoken dialects with some features in common. This is not a language, simply the raw material from which a language might be pulled together.

So basically it’s a case of “put up or shut up”. If you want there to really be a Scots language, create it, or rather lobby for the appropriate official institutions to do the necessary groundwork. Otherwise save it Burn’s Nicht and comic songs about escaped livestock.

here ye go … http://www.scots-online.org/grammar/index.asp

Here ye are … http://www.scots-online.org/grammar/index.asp

I think John above will confirm that a vespa is a wasp. 😉

Giusto 😉

The wee motorbike was so named because of the noise it makes 🙂

A Vespa was never a motorcycle, it is a scooter for yuppies.

The peculiar notion that Scots is not a language is a bit like creationism or climate change denial – the science is there, the facts are known, but it doesn’t stop those know-nothings who think otherwise from irritating the hell out of the rest of us.

A better analogy would be two zoologists arguing over whether the Hoodie as a race of the Carrion Crow or an entirely separate species.

They do interbreed where their ranges meet, but the hybrid zone as it’s called is limited to a narrow band. Very like the pile up of isoglossis seen in Scots-English dialects.

In the end it comes down to definitions, and there will always be marginal cases that just don’t fit.

Spot on.

In other words, does it matter?

Nobody denies that the climate changes; it always has, and always will. But there are no genuine science facts to back up global warming.

Mair proof at naebodie uises Scots onie mair: ma new book o poems owreset frae Classical Chinese ti Scots, “Staunin Ma Lane”, is oot in March (wi a publisher in England, mind).

See http://www.shearsman.com/ws-shop/category/1800-holton-brian/product/6053-brian-holton—staunin-ma-lane—chinese-verse-in-scots-and-english

Quite so, gn2.

Thanks for another excellent article on language, Paul, but reason and fact will never catch on: to the Cringers, Scots is just “slang”. It, and Gaelic, must be belittled/ marginalised/expunged as part of the Great Britishing Project, an extensive operation operating on a wide spectrum, from full-scale illegal invasions of other countries while waving the Union Jack to baking Victorian sponges in a marquee somewhere in the Home Counties while Mary Berry whips up some butter icing.

One of the delights of Scandi-Noir is hearing words we are so familiar with at home. My favourite is “braw”‘, which pops up regularly in The Bridge and others. I know it is given in dictionaries as a variant of English “brave” but I remain unconvinced. Can any speakers of a Scandinavian language enlighten us?

‘Braw’ means good, and I’d be surprised to find an etymologist trying to make out it’s from ‘brave’. It’s quite obviously from ‘bra’ and other scandinavian variants which also mean good.

By the way, bunnie in my dictionary, as ‘bunny’, is apparently derived from the gaelic word for rabbit.

I don’t know if it’s a coincidence but “bra”/”braw” also seems to pop up in the context of Manx Gaelic (“braew”, see http://learnmanx.com/cms/beginner_lesson_detail_256.html). I thought that was quite interesting – is it the influence of Scandinavian languages on Gaelic or the other way round?

Also in Welsh _braf_ and Breton _brav_, meaning ‘nice’, ‘fine’ etc. French was a very influential language.

I think it’s quite probable that Manx _braew_ is their version of _brèagha_, which looks like the descendant of Old Irish _breġḋa_ which means ‘worthy’, ‘fine’, ‘fair’ etc. See here :

http://www.dil.ie/search?search_in=headword&q=1%20bregda

Which suggests that the Gaelic words predate French influence … but who knows with Manx … Quoi ec ta fys?

Actually, according to most etymologists both Scots braw and Scandinavian bra are mediaeval borrowings of Old French brau ‘brave’

It’s also possible that Scots “braw” is derived from what in modern Scottish Gaelic is no2 “brèagha” but in modern Irish is “breá”, meaning beautiful, handsome or comely. Picking out individual words like these when they’ve all been around in contact with each other for centuries is interesting but not really very illuminating.

The Gaelic word for a rabbit (or a coney) is coinean (pronounced conyan).

The word ‘collie’ (a type of dog, of course), derives from the Gaelic ‘cuilean’ or ‘puppy’, ‘whelp’, ‘cub’. It’s also used in the Gaelic, affectionately, ‘my darling’. I called one of my dogs ‘Cuilean’ (pronounced ‘kull-in’) in honour of this rich language we take so much for granted and he certainly was my darling.

There is a rich vein of Old Norse in Scots words e.g. common place names, ‘Brodick’ derives from the Norse ‘Braid Vick’ meaning ‘broad bay’. As Scots then, we can easily guess what the capital of Iceland derives from, ‘Reykjavik’ or ‘reeky vik’ i.e ‘smoky bay’ just as Edinburgh is known as ‘Old Reekie’ (old smoky).

Whaur’s yer Muriel Grays noo? Thon blellum, bletherskite wee nyaff!

The National has recently given prominence to Scots poets, other than Burns.

My own favourite is David Rorie. Doric Scots.

An excellent wee book was printed by William Blackwood, Edinburgh in 1977 [ISBN 0 85158 121 8] by David Murison, called ‘The Guid Scots Tongue’.

Just reading it again recently from when I first read it in 1979, it is amazing how Scots attitude to their language has altered.

I really loathe the loony yoonies who so despise their own culture that they even deny a language’s existence.

One only has to look to Belgium to see that BelgiumFrench, Flemish Dutch and Walloon are all recognised languages. Many tried to argue that Walloon was not a language in its own right but a dialect of French. It was finally accepted as a unique language with its own cultural history and a ‘pure’ and ‘unique’ product of Latin, High French and Old German with a smattering of Old Norse for good measure.(as ‘pure’ as any language can be ‘pure’ or ‘unique’ to itself).

Scots is embedded in the legal system with terms only found in Scots legalese e.g. ‘behoof’ (behalf) and ‘furth’ (beyond) etc.

http://www.scotslanguage.com/articles/view/id/4669

I’ve always spelt “keech”, keigh.

Concise Scots Dictionary spelling – kich or keech.

Caroline: both CSD and Chambers have braw derive from brave. Considering brå sounds just like our braw and means the same, this seems rather strange.

Pretty similar to brawn = ‘physically strong’ or brawn = something the PM might be getting get stuck into.

What makes Scots special is special pleading. Clearly there are any number of languages within English in Britain and beyond. The only way to define languages fairly is pluricentrically as this is the only way to respect the perceptions of all speakers and not just the Lebanese nationalists who see the term Arabic as insulting.

Clearly Professor Aitken disagrees with you.

And Heinz Kloss disagreed with him tae. Jist as Hugh Trevor Roper disagreed with Edward Said.

Thanks for all the musings on “braw”.

Could I shamelessly plug one of the greatest 20th. century poems in Scots, which exploits all the language’s possibilities? It’s Sisyphus by Robert Garioch, and seems to me to sum up Paul’s points about this wonderfully plastic leid. It works best if you have the text in front of you.

https://scotlandonscreen.org.uk/browse-films/007-000-000-317-c

My uncle remembers doing his national service training, in England, he being the only Scots ‘draftee’.

On parade for the first time, the drill sergeant, also a Scot, announced;

‘For the next 3 months I am God Almighty and you are a bunch of wee keechs. McNeil will translate into English what ‘keech’ means,’ pointing to my uncle.

My uncle promptly replied, ‘Sir. You’re saying we are a bunch of wee shites, Sir’.

@Bibbit: meant to say your comments on Murison spot-on. When you combine his Scots Saws with Nicolson’s Gaelic Proverbs you really have the Scottish Ark of Ages.

Your drill sergeant sounds an earthy chiel, btw.

Some early linguistic studies by an objective source which supports the legitimacy of Scots as distinct language. The majority, if not all of the men interviewed from Scotland were recorded as native Scots speakers with English as their second language; there is also narrative descriptions which state they found speaking English quite challenging and for one almost impossible.

Enlightening stuff.

http://sounds.bl.uk/Accents-and-dialects/Berliner-Lautarchiv-British-and-Commonwealth-recordings

Heres what makes the Wiltshire language special.

http://sounds.bl.uk/Accents-and-dialects/Berliner-Lautarchiv-British-and-Commonwealth-recordings/021M-C1315X0001XX-0396V0

Nah, you’re linguistic simplistic Danny – up too late clearly!

Please address the evidence rather than the person Iain.

With pleasure. The empirical evidence is contained in the vocal recordings and notes on those interviewed Danny; notes taken by someone who neither shares your or my political views. It is therefore an OBJECTIVE academic study which evidently accepts the legitimacy of Scots as a distinct European language. The recordings you selected attempting to conflate the speech of the English shires with that of the Scots interviewed is only an illustration of your inability to accept Scots native speech is linguistically distinct to that of England, The Scots language has been around for a very, very long time Danny – even longer than the Scottish cringe i’d venture!

It acceots the perception that when someone says “faither” and is from Lanarkshire, its a word from a different language than when they say it and come from Shropshire. The recordees would have named their own language just as a Lebanese nationalist would when calling it Lebanese rather than Arabic and saying the same words using the same structures as a Lebanese Pan Arabist.

It certainly has and is as old as many other Northern English speech varieties which also share the same level of divergence from standard English. I dont mind what people call it as long as they respect the rights of others in a pluricentric manner.

It is not perception Danny, it is an OBJECTIVELY recorded & notated fact! Scots borrows as much from Gaelic as it does from its German progenitor.

Its politeness on behalf of the Edwardian era Germans and respect for the views of the participants. They saw their English as being Scottish. Scottish is the word noted by the results for speech varieties very similar not only to Northern English, but parts f the Midlands of England as well and these have all changed drastically in the last century as shown by the example fom Essex which was much nearer to Norfolk than to London. Some areas that are today in London would have sounded like rural East Anglia and Glaswegian sounds nothing like Rab C Nesbitt or River City. They were more intersted in the sounds than the names by the look of how its presented and based the names on what participants told them.

And Wenglish des from Welsh, Cockney from Romani etc. The Gaelicinfluence is arguibly the main reason for seeing Scots as different from other Northumbrian dialects.

I am not disrespecting English dialects and i find it fascinating that somebody from Codicote in Hertfordshire then sounds so very different to those who are born and bred there now… i know this. I also know their English dialect has never drawn from the same linguistic influences Scots has, and these influences combine to make Scots quite distinct! Sorry, but i do not accept your assertion that the differentiation made between Scottish & English speakers was based on German (Edwardian) politeness, the notations are based on observation and linguistic tests including pronunciation on generic text. I’m afraid that you will not dissuade me that Scots is simply another English dialect – it is evidently not and the influences which have shaped it underline this difference.

In addition It’s not unreasonable to say that with the advent of mass communication (in the UK) the English dialect/speech has purposefully been driven to ape a dialect originating from a very small strata of English society which is a disservice to both the English and Scots languages..

Then you are maintaining a faith based position because thats the most logical reason for precisely the same wording and grammar being treated separately depending on what the individual participants said they were speaking. I see no logical reason to assume otherwise.

Heres an example of the Wolverhampton language. (Black Country Yam)

http://sounds.bl.uk/Accents-and-dialects/Berliner-Lautarchiv-British-and-Commonwealth-recordings/021M-C1315X0001XX-0402V0

Gloucestershire language (“There wur a mon, to I and agin there be I, thy, thee, the faither etc”)

http://sounds.bl.uk/Accents-and-dialects/Berliner-Lautarchiv-British-and-Commonwealth-recordings/021M-C1315X0001XX-0448V0

Its also clear that the simplistic division of English languages in Britain into English and Scots is hard to maintain in the light of the Northern dialects in England sharing so many features with those in Scotland, Shetland speakers seeing their dialects as not having anything to do with Scottish ones and being English, and the myriad of divergent dialects across the Midlands of England and West Country and East Anglia inclusive of Essex. Comparing the furthest North dialects to the standard of Modern English will of course give the result that they are separate from it but this doesnt mean all other dialects werent equally variant and part of a gradual continnum of English dialects.There is a special case for seeing Scots as a language and it is political ie that it was the offical standard written language of an independent state and was written and read as such. This is no longer the case but was so and hence the belief among First World War soldiers that they were apparently speaking “Scottish” (although this may have been lost in translation by German academics recording them and other English speakers from across the UK.) If people want to call their dialect Scots then please do. However others dont and they have as much right to see their speech as English, which going by the last census, its probable as many speakers of Scots dialects do.

Iseabail Macleod, Editorial Director of the Scottish National Dictionary Association 1986 – 2002, stated in an interview with the Scots Magazine in December 1997 that “Scots covers everything from dialects which the English — or even other Scots — wouldn’t understand, to the way we’re speaking just now, which is English with a Scottish accent.”

Thats a big part of the problem. If the definition was narrowed it would have more of a reality as a definition.

All traditional dialects of English have Abstand (linguistic distance) vis a vis Standard English – indeed that’s what allows us to define them as dialects. Scots likewise has Abstand vis a vis Standard English. What Professor Aitken was arguing was that in terms of Abstand Scots is more differentiated from Standard English than other English dialects, that in terms of both quantity and quality Scots stands apart from the general run of English dialects when it comes to its raw linguistic differentiation from Standard English.

One measure of this is the simple fact that it is possible to describe the vowel systems of English dialects in terms of their differences from the vowel system of RP. This is actually the standard way of doing things in English dialectology. However it is not possible to do this for Scots as the Scots vowel system is organised according to fundamentally different principles (Aitken’s Law).

Another is the great wealth of Scots vocabulary, which quantatively exceeds that of anything else which could be described as an English dialect.

A point which you fail to address is the existence of the Scots-English linguistic frontier. This is the only sharply demarcated “dialect boundary” anywhere in the English speaking world. By itself its existence sets Scots dialect off as a markedly distinct group apart from the general run of English dialects.

In terms of Abstand, Scots can only be compared with Creolised varieties of English – and there is also considerable debate about whether these varieties are in fact English or languages in their own right.

However it’s not merely the existence of Ausbau which is crucial in the determination of whether a speech variety is a dialect of a particular language or a language in its own right, it’s also the existence of Ausbau. Ausbau is the conscious elaboration of a speech variety for literary or other purposes. Scots possesses Ausbau in ways which no other variety of English remotely approaches. There are registers of Scots – nowadays these are attenuated but they do still exist. There is a formal written Scots which attempts to supercede dialect differences within Scots. There is (or rather was) legal Scots. There is no such thing as a formal register of Geordie or Cockney.

Another manifestation of the Ausbau of Scots is the enormous quantity and quality of Scots literary output. Again, there is nothing which remotely compares in any English dialect.

It’s this combination of linguistic differentiation, plus a history of elaboration for literary and other purposes which allows us to say that Scots is a language. What its own speakers call it is certainly interesting from a sociolinguistic point of view, but not a reliable guide to its classification. After all, until the 1950s many speakers of the Tibeto Burman Tujia language and the Tai Kadai language Zhuang were convinced that their languages were dialects of Chinese. When a speech variety is unwritten or no longer written, its speakers will often identify with another more prestigious variety.

What it shows is that its on the outer suburbs of the indigenous English dialects preglobalisation. That makes sense and is really that surprising. Its quite clear to any learner of English speaking to a Scottish speaker of English (or a Geordie) that the vowels are the most tricky part of understanding them and Ive had this problem over the years on several occasions.

Comparing a Tai Kadai language to Chinese with Scots and Modern English is rather absurd. Scots was an English language when it was codified. It was believed to be English by its own speakers for many centuries and still referred to as such on occassion in the Reofrmation era not because it wasnt written but because it shared an English origin with the Southern codified language and all the dialects in between. Furthermore Northumbrian was still spoken across the North and Geordie vowels are much nearer to Scottish ones than to those in the South of England.

Until 1707 the official language of Scotland was ‘Scots’. It wasn’t an affectation. It was a fact of life. The highest judges and the highest lairds all spoke the same language as the poorest beggar.

In my profession I have read old title deeds dating back to before 1707, and older court records. I can assure you that Scots was not an English language, derived from England. How could it be? England had no currency in Scotland jjust as French and German had no currency in Scotland.

Furthermore none of your English dialects were ever the language of a sovereign nation with a sovereign church, recognised by other countries and the pope of Rome, with its own ambassadors to other sovereign countries, including England..

You sound like the cultural imperialists from French speaking parts of Belsium who for years sneered that Walloon was not a language in its own right but a dialect of English.

Addendum last word Englsih should read of course ‘French’

The cultural imperialism was against the Gaels by the people in Embra who started calling them Irish when they changed the name of their own language.

From original Government papers regarding the Statutes of Iona etc:

“THE QUHILK DAY it being understand that the ignorance and incivilitie of the saidis Ilis hes daylie incressit be the negligence of gaid educatioun and instructioun of the youth in the knowledge of God and good lettres: FOR remeid quhairof it is enactit that everie gentilman or yeaman within the saidis Ilandis or ony of thame having children maill or famell and being in goodis worth thriescoir ky, sall putt at the leist thair eldest sone or, having na childrene maill, thair eldest dochtir to the scuillis in the lawland and interteny and bring thame up thair quhill thay may be found able sufficientlie to speik, read and wryte Inglische.”

(Statutes of Icolmkill,1609)(Collectanea de Rebus Albanicus pp119-20)

Austria is a sovereign country with lots of Christians so presumably a sovereign kirk tae.

One scribe in 1609 writes ‘Inglische’ and you hang your whole argument on that peg.

You have now entered a whole new argument concerning the eradication of Gaelic by anglized lairds.

You are dancing on the head of a pin. A wee, wee pin.

Please show links for your ‘dialects of England’ having their own sovereign courts of law where said dialects were the written currency in treaties with other sovereign nations like France and Germany etc.

I am sure if I could be arsed I could find old 1609 manuscripts from England written in French, the official language of the English court. Irrespective of those deeds and references to court French, the common people of England were not speaking court French but their dialects of English apart from Cornwall, where they spoke a separate Gaelic language, just as Scots spoke Scots or Scots Gaelic.

I didn’t realize languages needed to be court languages of sovereign states to exist separately from other ones. Basque doesn’t whereas Austrian German does.

The quote was from the Statutes of Iona, not just any old document written by someone confused as to what they spoke.

Actually no, they’re not. Geordie, like the vowel systems of other English dialects, has a series of short vowels and long vowels which are qualitatively distinct. Scots dialects have only one vowel series in which vowels can be quantatively long or short without qualitative differences depending on their phonetic environment.

I’m not comparing Scots to a Tai-Kadai language. I said quite clearly that speakers of one Tai-Kadai language regarded their speech as a type of Chinese. But I think you knew that.

I said Geordie vowels are the most difficult aspect of the dialect for foreign speakers of English too understand not that they were long.

Ah! Abstand (linguistic distance) vis a vis Standard English. What about Abstand compared to other non-standard varieties of English and to the whole range of English too? Its seems English is being redefined as Standard English only in order to produce some noticeable Abstand that then can be used to justify the languageness of Scots. By that route it can be argued that any non-standard variety of English has Abstand and is thus not English but a different language.

Scots has Abstand versus Northern English dialects – that’s precisely what the sharply delimited Scots-English linguistic border defines. However when deciding whether a speech variety is a language or a dialect, the question isn’t merely one of Abstand, but a combination of Abstand and Ausbau. Scots is unique in the range of “English dialects” in having both.

Then its the next stage in the chain of English which again isn’t surprising.

There’s a clear and sharp break in the chain right along the Scottish-English border.

Its only a break if you choose to use that as a marker of one. Vowel length varies in other languages too:

http://scholarworks.umass.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1084&context=linguist_faculty_pubs

The Scots-English linguistic frontier is not merely the isogloss for vowel length. It is the greatest bundle of isoglosses anywhere in the “English speaking” world, and as such is unique.

Thats because the colonies where English arrived were either first colonized by speakers from England in the case of the United States, or by speakers after the union when the Scots who went there and took a leading role were desperate to take part in the converging of the English languages started by the James VI and John Knox. There are dialects of Arabic that are unique in the Arabic speaking world. Its a fairly shuglie stick as a basis for being a separate language when it has no orthography and its default standard remains modern English.

You keep pointing to single features and saying “But XYZ is found in this variety that’s recognised as a dialect” as though that proves your point. The point however is that it’s the totality of linguistic differences plus its conscious elaboration as a language plus its use in a wealth of literature that has no comparision in any other “English dialect” that makes Scots a language. You keep exhorting others to address the evidence, take a leaf out of your own book and address all the evidence, not just isolated parts of it.

You keep pointing to a single feature as a signifier of Scots being a separate language when every other indicator shows it to be forms of English today. It was a written language because it was the state language of a pre modern English European state but thats no longer the case and it has been the conscious intent it appears of Scots writer and thinkers since at least the eighteenth century and arguably earlier if you count John Knox, to reconverge the languages into the single one they came from. It was a language for state purposes in an age before English became so dominant globally. That isn’t the case any more and it doesn’t function as a unified language de facto due to the use of modern English between people who dont know each other and come from different dialect areas, just like across the rest of Britain when English is used.

Danny, you don’t seem to have accepted the thrust of WGD’s article, or Prof. Aitken’s research. Our dialects are dialects of Scots, not English. And then, of course there’s Gaelic, which, as Iain has pointed out, has contributed a prodigious number of words to Scots.

But thanks for the Lautarchiv links: most interesting. Lots to think about here.

Levantine Arabic owes the same debt to Aramaic and has a far more divergient grammar than is the case between Scots and English dialects in Britain today. Its a question of definition in the context of a non standard default other than Standard English for the dialects. I also have to assume that the readings from the recordings were all written in the same language. It was at that time a language with far more traditional dialects across the whole of Britain which seem to have had no national border. If they had, terms like “faither” wouldnt have been used so far south of it as is apparent in the recordings.

As you said, it’s a “question of definition”. But whose definition? You seem unwilling to accept linguistic difference and are trying to smooth them out to meet some English/Pan-British bench mark. I would have to ask, what great literature have these English dialects you mention produced? And then compare, if you can, the literature in Scots. We are a different nation and our languages have developed differently: quelle surprise.

You might wish to reconsider what WGD and Prof. Aitken have argued in this respect.

Thats precisely what I have done. However the definition of language is one that contradicts the empirical data of how people were speaking in 1916. I am unable to agree that there was a clear differentiation between two languages at that point in history. I do accept that is and was a language, however there are several caveats to that: It was an English language in the sense that Swedish is a Norse one and was one of the two standard English languages of Britain in the pre-global English phase of English (the other one being Southern) and it was already merging back into being a single English language at the time when it had its golden literary period as John Knox chose Southren as his language for spreading religious change across the English speaking parts of Scotland as well as the parts being Anglicized at the expense of the other Scots language. It was this language that had originally been known as Scots by the English speakers in the extreme South East of Scotland, who had regarded themselves and their language as English, until a few rulers decided to swap the names around and starting calling English Scots and Scots Irish. What I differ on is whether there are any other languages in English across the UK in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth and if language is to be defined as non standardized non written, that is a valid question as language doesn’t exist according to linguists. Its simply a perception and definition of speech varieties. The real reason there was a Scots language discovered via those recordings above was in other words, because of the faith of English speakers in Scotland that their English language was apparently called Scottish, which is even more nebulous than the term Scots.

Oh dear.

“You might wish to reconsider what WGD and Prof. Aitken have argued in this respect.”

And repeat.

The definition of Scots has nothing to do with these recordings, which are extremely late. Your last sentence makes no sense whatsoever.

I think we can agree that you think Scots is not distinct from dialects of English and I, amongst others much more distinguished, don’t?

If so, we can just leave it at that.

The definition of Scots and the promotion of a belief that English isnt the name for them is precisely the reason for Scottish English speakers telling German recorders that when they say the same sentences as someone from Lancashire that its called “Scottish” I would suggest. Its definition is as the language of Scotland as decided by the kings who set out to change the state language from Scottish Gaelic to Scottish English.

It only makes sense when the Scottish cringe over defining Scots dialects as English indigenous speech is dropped.

Heres an earlier recording from a speaker and writer of the period before the Scottish cringe over the E word for the English language had been fully established.

‘The Goldyn Targe’ by William Dunbar (c.1420-c.1513):

O reverend CHAUCERE, rose of rethoris all

(As in OURE TONG ane flour imperiall)

That raise in Britane ever, quho redis rycht,

Thou beris of makaris the tryumph riall;

Thy fresch anamalit termes celicall

This mater coud illumynit have full brycht.

Was thou noucht of OURE INGLISCH all the lycht,

Surmounting eviry tong terrestriall,

Alls fer as Mayes morow dois mydnycht?

“It only makes sense when the Scottish cringe over defining Scots dialects as English indigenous speech is dropped”

As far as the Scottish Cringe is concerned, I fear you are looking through the telescope from the wrong end, Danny.

Nice talking to you, but we can only repeat ourselves so often before entropy takes effect.

Bonsoir, mon vieux.

At least Im chosing to define the phrase for myself. Normally the meaning is a cliched given to back up the tired rhetoric of a language being something necessitating an army and navy etc. (oddly enough Gaelic and Welsh have neither).

Seriously! The Scots language and your terror of its legitimacy will not decide Scottish Independence; that will be driven by the growing belief that Scots people can take care of their own affairs more effectively and responsibly than a narrow strata of English society who dismiss anything outside their culture as worthless and compassion as weakness; your contribution in their support will not derail the Scottish democratic enlightenment Danny, it really wont.

The last Enlightenment was a period of scientific racism and imposed modernization at the expense of culture ironically where writers such as John Pinkerton were mocking Scottish culture by misrepresenting its history and Scots speaking Enlightenment leaders themselves were continuing the convergience of their English dialects with the newly popular Southern English one . This of course was nothing new. The Rennaisance was also a period with a hunger for Englishness where we have William Dunbar looked to English as his model because thats what his language essentially was. He looked to Europe for a lexicon to express his version of it and looked to Gaeldom for a negative comparison rather than England. The modern Mathew Fitt type Scots is more of a sociolect and has more do with the poetry of working class Merseyside and Brummie poets than it has with such world views. If this democratic Enlightenment will be any better, then it must accept a pluricentric definition of things to avoid an imposition of a new stranglehold over freedom of speech against those such as the guy outside a ub in Embra who told me in no uncertain terms that his own borders dialect was English.

In Luxembourg they get on and develop their language rather than just talk about it in German. This doesn’t seem to be the case in Scotland with Scots without a standard orthography being taken seriously, all there is is an observation of vowel length as a sort of totem of difference from English. This is frankly a sop to the Scottish cringe as I would define it, namely that English cant be the language people use because they are Scots. The term “Scots” is a catch all term today in the dialects for people, nation and language and its all based on how long their vowels might be. Id rather see a standard official form of it created and taught in schools as a language so that all the dialects had something other than modern English to be part of and not just based on old poetry. This of course would necessitate a debate about what exactly that artificial form should be but I know its supported as a goal by such campaigners for Scots as John M.Tait who has written extensively on the problems with the Scots language campaign movement as it stands. All standard orthographies are artificial and yet somehow, Scots is expected to evolve one naturally.

Heres an excellent article by him on the topic:

https://sites.google.com/site/scotsthreip/robertsonianism

Give me strength!!

I recall my late father observing in relation to a sign on the ‘bus ;-‘Please mind your head when alighting from the vehicle’, (or words to that effect) :- ‘I wonder if any body has got off the ‘bus and left their head behind?’

‘Where do you stay?’ meaning , ‘where do you live?’ often baffled my English colleagues.

Hands off our local linguistic foibles, I say.

Interesting comments, but I think I’ll come back when Danny has run out of breath… next June mibbies?

Och Im sair affronted. Mind ye dae. I wuild caw cannie but I keep gettin repones tae thum.

You are one boring, self-absorbed windbag. I’m away to watch some paint dry, it’ll be more interesting and certainly more educational.

I dont make personal comments though.

Go suck an egg.

Charming

Must admit, my scrolling was increasing at a pace.. 🙂

Ditto!

Id prefer to see Scots treated as a serious language rather than a definition of anything between the most impenetrable dialects (say of Shetland which was ironically never thought of as Scottish until the nineteen-eighties by its own speakers) to English with a Scottish accent as seems to be the case according to the quote mentioned earlier in this discussion. When it had an orthography, some of its most celebrated writers and most important documents used the term English to describe it whilst writing in a way that could be learned by a French speaker with no English. Today the writer of the first Scottish coursebook suggests to learners not to use Scots when first visiting the country as it may be perceived as “mockery”. This suggests to me that the attitudes that need to change are the ones promoted by campaign groups that don’t want to develop an artificial orthography to ensure that it will again be a separate language from English. Vowel length must surely be shared between Scottish English speakers and broad Scots dialect speakers and if this isn’t the case, then the quote from a Scots language expert mentioned earlier in this discussion wouldn’t make much sense as if Scots is a catch all term for any form of English with a Scottish accent, then they must be sharing the same vowels (apart from Jackie Bird and her diphthongs).

I’m sitting here in my baffies wi a sair heid. I love the auld Scots words and I’m delighted that we are all keen to keep them alive. The academic side is largely lost on me but the power of the words in drawing us together is clear. A shame for those who can’t see a value in that. Lateral thinking is not their forte.

A nation is more than words and that will always be lost to those unwilling to see arthur. 😉

Auld Scots wurds cuild be uised mair hame abouts the day insteid o jist on Burns Nicht gin thur wis a stannart orthographie fur the leid.

Thats the case for many nations sharing languages.

I think one major problem for Scots as a language is the notion held by some speakers that its more a case of auld Scots wurds than an entire language.Its not me that created this situation but it is something t think about when trying to support it as a language. If I could do a course in Scots to become capable of speaking a standard form, Id be very happy. It would mean I could use it in Germany or Spain instead of English and know I was avoiding using English entirely, which unfortunately isnt the case at present.

I also support real efforts to develop it again as a language for this reason.

I wis on the brig wae Captain Kirk and Spock and Sulu tae,

whin a seen the trip back tae the Earth wis affie lang tae gae.

A Klingon klang tae starboard side a’ nippin at ma heid

so a took a phaser in ma haund an nou thon Klingos deid.

A weir brak out atween our warlds an lasted twenty year

and in thon weir a lost masel sae monie comrades dear,

but nou am back in Glesga toun a dancin in George Square

een though Ive been thru sic a fecht thits turnt me gray frae fair

Ive lairnt tae see the ither side o fremmit Klingonkind

a laison sair and sairlie lairnt thit humankind maun mind.

Soooo having read the article I did an experiment in my head that I’d like to share. Granted it’s only one verse but I think you get the gist here.

How’s this for beautiful, evocative poetry?

……

Oh, you quiet, shy animal,

How worried you must be!

Please don’t run away from me!

I would never dream of hitting you with a big stick!

….

Who else just read that and had a big flashing NOPE hit them?

I rest my case.

Try Detective Columbo’s lines speaking like Bertie Wooster and you’ll have the same result 🙂